AboutMoby

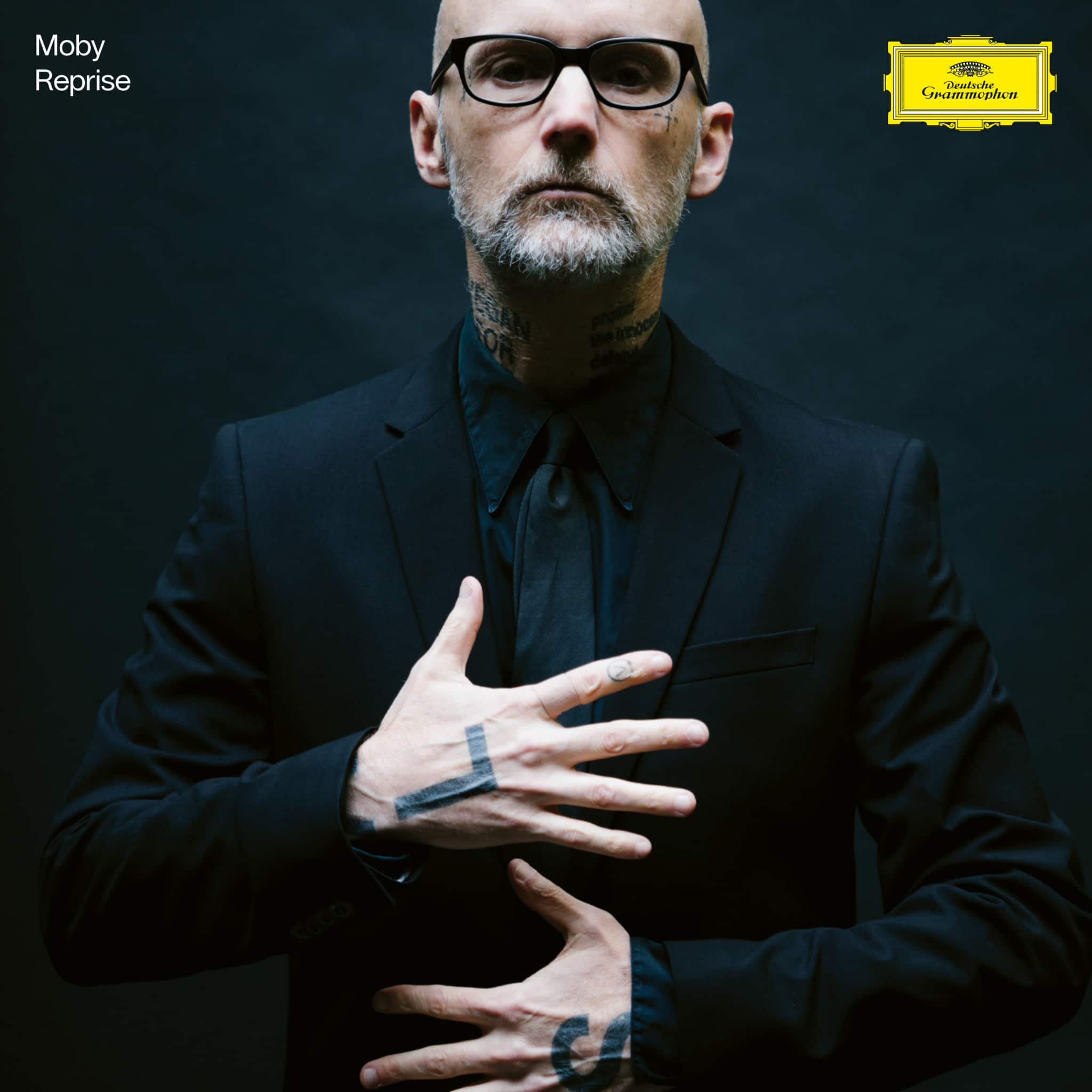

For Moby, "Reprise" is an opportunity to delve into the personal highlights of his work in a completely different way. Together with the Hungarian Budapest Art Orchestra, he has reinterpreted some of his most famous rave classics. Some of these versions are now sparser, slower, more vulnerable, while others exploit the brilliant potential of an orchestra. Three decades after Moby's career began, "Reprise" is less a greatest hits album and more a reflection on how art can adapt to different settings and contexts over time.

30 years ago, Moby was an underground DJ in New York. He became widely known for "Go," an electronic dance track. Then as now, however, Moby's path remained unconventional and winding, full of dizzying peaks and dark valleys. Only his art remains constant, born of curiosity and disappointment, fun and possibility. Although he looks back on one of the longest and most idiosyncratic careers in the music of his time – with over 20 million albums sold – he actually refuses to even think about a career. "I know it sounds simple, but I just love to make things," he says on the phone from his studio in Los Angeles, and his honesty is disarming. "Strangely enough, I don't like to take myself or my career too seriously. I could easily name 500 musicians and songwriters whom I consider much better than myself. I'm simply lucky that I occasionally work on music and it seems to appeal to someone."

The idea of revisiting and shaping songs from his past came about seven years ago, Moby recalls. He had finished with the mighty machinery of world tours; he hated them. Instead, he had opted for stripped-down acoustic performances in neighbors' gardens and on small stages. "There was this unvarnished vulnerability," he says of the modest sets, "and it was precisely this emotional directness that appealed to me, especially in contrast to the manufactured pomp of established big concerts."

After Moby attended a Bryan Ferry concert in Los Angeles, he got talking to the concert planner of the LA Philharmonic. "She asked me if I wasn't interested in doing an orchestral live set with the LA Philharmonic. Of course, I thought she was pulling my leg, and replied that it was probably more for real artists." His counterpart disagreed. And in October 2018, Moby made his orchestral debut with a gospel choir: Gustavo Dudamel was on the podium and Eric Garcetti, Mayor of L.A., sat at the piano. That evening, Deutsche Grammophon approached Moby backstage to ask if he could imagine an orchestral album. And Moby agreed. He had grown up with classical music. Before playing in punk bands and producing his own electronic music, he had even studied it.

As often happens, the recording of "Reprise" started small – in Moby's studio. He selected the titles and worked out the orchestral arrangements in a first draft. It continued in Studio 3 of the East-West Studios in Los Angeles (Brian Wilson had recorded "Pet Sounds" here), to record piano and guitar, drums and percussion, and a chamber orchestra. After that, Moby moved the production to Hungary, where the Budapest Art Orchestra was waiting. Moby, however, remained in the States; without any experience with orchestral recordings, he would only have gotten in the way, was his last-minute opinion. "My presence in Budapest would have been more ceremonial; there was no real reason for it," he explains. "I had done the essentials of the arrangements in L.A.; for the orchestration, I had to put them in the hands of someone who actually knows how to get 100 classical musicians to play together."

The engagement with the orchestral version deepened his reflections. What is the meaning of music, especially when it doesn't fit current trends? "Sorry, but this may sound obvious, but for me, the meaning and purpose of music lies in conveying emotions, in sharing an aspect of the human condition with someone who is listening." Although Moby likes some current pop and hip-hop records, he is frustrated by the lack of sensitivity shown in many contemporary pieces of music. "I can certainly enjoy some of what you hear right now, but I long for the simplicity and vulnerability that can be achieved with acoustic or classical music."

And he continues: "Of course, I don't want to sound like one of the old folks, but for me, today's music rarely feels authentic. Every indie rocker wants to appear cooler than he is, every rapper harder and more frustrated, every pop musician sexier. But sometimes you just want direct, honest communication. If you bring acoustic and classical instruments into play, the possibility of an immediate, sensitive exchange increases. I don't know if I achieved that with 'Reprise.' But it was my goal."

Adjectives like beautiful, grand, and breathtaking come to mind when listening to the pieces – "Natural Blues," for example, with its acoustic strumming and a few violins introducing the vocals of Gregory Porter and Amythyst Kiah, or "Porcelain," which the brilliant Jim James expresses with such depth, or "Extreme Ways," where Moby lays everything bare. These meditations, often accompanied by plaintive strings, are placed in a new context and yet bear witness to the original and the deep, broad scale of emotions found in Moby's work.

"The Lonely Night," with Kris Kristofferson and Mark Lanegan, is one of Moby's personal favorite tracks on the album: "Few people know the song, but it's so important to me that there would have been a fight if someone at the label hadn't wanted it – and I'm a pacifist." When selecting the titles, Moby was interested in a balance between the popular and the private aspects of his music. "Every musician wants people to listen to the obscure B-sides, but of course, the audience wants to hear the songs they know and love." For the hits on "Reprise," Moby imagined what the re-arrangement would sound like for a fan. And for the singers, he paid more attention to the emotion in the voice than to the artist's fame or virtuosity.

Moby himself cannot say how the project, in which he brings songs from his past into his present, has affected him. From others, he has learned over the years that his music exists in a place between sadness and joy, yet it is neither overly desperate nor ecstatic. "There were such titles, without hope or in euphoria, but mostly my music tells of the bittersweet in-between." This is also the case on "Reprise." The music honors the past, deepens the present, and leaves open the question of what comes next.

A highlight on the album is the cover version of David Bowie's "Heroes," a piece Moby calls a favorite song and which he once played with Bowie in his apartment. Bowie, a New York neighbor on his street, was like an older brother to him. "If you cover 'Heroes,' you might as well tackle the Sistine Chapel or 'The Godfather.' 'Heroes' is one of the five most popular songs of the last 100 years. What I'm doing there is a challenge and, of course, presumptuous. I still wanted to do it because I love 'Heroes' so much. That experience of playing 'Heroes' with David on acoustic guitar is one of my fondest memories," Moby says. "We both sat in my living room with our coffee. Unfortunately, we never recorded that. The acoustic version on the album is like a love letter to that memory." Mindy Jones' voice openly reflects this.

And in other respects, "Reprise" is a love letter – to his own idiosyncratic life and the career that resulted from it, written like by Proust. But "Reprise" is also a thank you for what he was able to create, in front of people and in places he hadn't expected. And sometimes there are quiet echoes of the place where it all began – alone at home in a room with a few machines. "My music was created in a monastic, austere way," Moby says. "It's strange to write something late at night alone in a small room and then release it into the world, where it takes on a completely different life. When I used to be on tour and played a song like 'Porcelain' on stage in front of 500,000 people and they all sang along, I thought: 'Huh, I wrote that all by myself at two in the morning and never expected anyone to ever hear it.'"